If you've ever been to Boston, you know we've got a lot of old stuff. Well, about 20 years ago, I bought a condo in a 120-year-old building. The toilet wouldn't flush very well. Old toilet, old house — I figured I'd just replace it and see if things improved. Bought a new toilet, had it delivered, plumber showed up.

He took one look and said, "I can't do this."

What I hadn't really noticed before was that the toilet was mounted below the level of the floor, set into concrete or plaster or something. I asked how much it would cost to actually replace it. His ballpark guess? $25,000. (WHAT?!?!)

That pretty much wrapped it up for the toilet replacement project.

Fast forward a couple years and we decide to renovate the bathroom. For context, the bathroom is just off the kitchen, which had a funky drop ceiling and some weird wall panels — it's an old house and it was a bit of a fixer-upper. (No biggie, right?)

We get a quote for the bathroom renovation. It wasn't $25k anymore. It was $50k for the bathroom... and then another $50k for the kitchen. (HOW?!?!?)

Here's what happened. To fix the toilet, you had to replace the floor in the bathroom. Because the bathroom is attached to the kitchen, you also had to replace the floor in the kitchen. Replace the floor in the kitchen, and now you have to do something about the weird walls (balsa wood panels concealing a disaster of crumbling horse-hair plaster). Fix the walls, and now you have to fix the ceiling — which turned out to be not just one drop ceiling but two drop ceilings stacked on top of each other.

The ceiling thing was the real mind-blower. Over 120 years, no one had ever done an actually good job at fixing anything. Rather than dealing with the original crumbling ceiling, someone put in a drop ceiling. And then when that drop ceiling got too gross, they... (drumroll) ...just put in another drop ceiling. (🤦♂️)

A decade-plus later, it all got fixed. But it turned out that I'd basically bought "Casa de los Tech Debt".

What Is Technical Debt, Anyway?

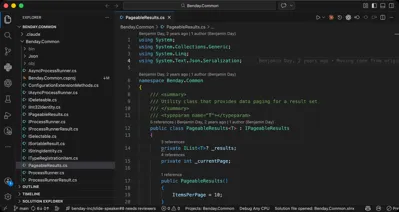

Technical debt is a thousand little bits of not-quite-done. It's the scar tissue of software development — bandaid fixes on top of quick repairs held together with duct tape. And when you try to start fixing it — "paying down" your tech debt — you find that every layer of stuff you try to fix exposes another layer of stuff that needs to get fixed.

It's endless. It's my condo.

The term "technical debt" comes from Ward Cunningham, one of the original signers of the Agile Manifesto. The metaphor is financial: sometimes you take on debt intentionally to move faster now, knowing you'll pay it back later. Ship the feature with a shortcut, clean it up next sprint.

Except... we almost never pay it back. The "next sprint" never comes. And just like financial debt, technical debt accumulates interest. The shortcuts make the code harder to understand, which makes the next shortcut more tempting, which makes the code even harder to understand.

Drop ceiling on top of drop ceiling.

Why Your Boss Doesn't Care (And How to Make Them Care)

Here's the problem: developers feel technical debt every day. It's the friction that makes simple changes take forever. It's the fear of touching certain parts of the codebase because everything is connected to everything else in ways nobody fully understands.

But when you tell your manager "we need to address our technical debt," their eyes glaze over. It sounds like you're asking to spend time on stuff that doesn't ship features. It sounds like gold-plating. It sounds like developers wanting to play with shiny things instead of delivering business value.

You're speaking different languages.

Technical debt is absolutely a business problem. But you have to translate it into business terms. Here's how:

It's a delivery speed problem. "Features that should take a week are taking three weeks because every change requires working around problems in the existing code." That's concrete. That's measurable. That's money.

It's a predictability problem. "We can't give you reliable estimates because we keep discovering hidden problems mid-development." Managers hate surprises. Unreliable delivery timelines make planning impossible and make your team look incompetent (even when the real problem is the codebase).

It's a quality problem. "We're shipping bugs because the code is so tangled that it's hard to test and easy to break things accidentally." Bugs cost money — in support time, in customer trust, in emergency fixes that derail planned work.

It's a people problem. "Our best developers are frustrated and talking about leaving because working in this codebase is miserable." Hiring is expensive. Losing institutional knowledge is expensive. Developer turnover is really expensive.

It's a risk problem. "There are parts of our system that only one person understands, and if they get hit by a bus, we're in serious trouble." This one gets executives' attention.

The Toilet Problem

Here's the other thing you need to help your boss understand: technical debt isn't fixed by a "cleanup sprint."

Remember my toilet? The plumber's original quote was $25k. By the time we actually addressed it, we were into $100k+ of cascading repairs. And there was no way to know that up front. You couldn't just "budget for the toilet fix" because the toilet fix wasn't really a toilet fix — it was a bathroom fix, which was actually a kitchen fix, which was actually a "multiple generations of deferred maintenance" fix.

Technical debt works the same way. You think you're going to clean up one module, and you discover that module depends on another module that's even worse. You fix that, and now you've broken assumptions that three other modules were relying on.

This isn't an argument against fixing technical debt. It's an argument for being honest about what fixing it actually looks like. It's not a project with a neat scope and timeline. It's an ongoing investment. It's maintenance. It's the cost of having a codebase that doesn't actively fight against you.

The Condemned House

There's a crash-into-the-wall moment with technical debt, and that's the "rewrite project."

In house terms, it's when the building is condemned. It's no longer safe to occupy. Fixing it is such a giant question mark of infinite uncertainty that the owner decides to tear it down and build from scratch.

In software terms, it's when the codebase is so far gone that leadership decides to flush their years of investment and rewrite the application from scratch.

This is the ultimate in terrible ROI. You throw away everything you have, and then you invest enormous amounts of time, money, and effort into just getting back to zero. You're not adding new capabilities — you're recreating the capabilities you already had. And you're doing it while simultaneously maintaining the old system that customers are still using, because you can't just turn it off while you spend two years rebuilding.

Rewrite projects are also some of the riskiest projects an organization can take on. They take longer than expected (always). They cost more than budgeted (always). And there's a real chance they fail entirely, leaving you with two half-broken systems instead of one.

You want to avoid the rewrite project at all costs. It's a stone-cold loser of a business proposition. If this starts looking like the right option, stuff is seriously messed up.

What Actually Works

So what do you do? A few things:

Stop making it worse. The most important thing isn't paying down existing debt — it's not accumulating more. Every new feature is a chance to either add to the mess or leave things a little better than you found them. The "boy scout rule" — leave the campsite cleaner than you found it — applied consistently over time makes a real difference.

Make it visible. Track the impact. "We spent 40% of this sprint dealing with issues caused by the legacy authentication module." When you can show concrete numbers, the conversation changes.

Tie improvements to business work. Pure "tech debt sprints" are a hard sell and often don't happen. But "we're adding this feature, and while we're in that part of the code, we're going to clean up X and Y so future changes are faster" — that's easier to justify. The improvement has a business reason attached to it.

Be honest about the scope. Don't promise a quick fix when you know (or suspect) it's going to cascade. My plumber was honest with me about the $25k. I didn't love hearing it, but it was better than getting surprised mid-project.

The Oil Tanker Three-Point Turn

One of the best ways to turn around your tech debt problem is to start writing unit tests. Yes, unit tests — not integration tests.

I can already hear you: "But Ben, our app is a giant untestable monolith... that's impossible!"

No. It's hard. But it's not impossible.

It takes commitment and discipline. You're not going to unit test the whole application overnight. But you can start. Every new feature gets unit tests. Every requirements change gets unit tests. Every bug fix — before you fix it, write a test that fails, then make it pass. Every — single — line of code that you touch — gets a unit test.

Sounds gross...but compare the level of effort to start writing unit tests for new work versus rewriting the whole application. One of these is a slow, steady investment that makes things incrementally better. The other is betting the company on a multi-year project that might not even succeed.

This turnaround won't be fast. It'll be like an oil tanker doing a three-point turn. But give it a year. You will see real improvements. The parts of the codebase that have tests will be easier to change. Developers will be less afraid to touch them. Bugs will get caught earlier. And slowly, methodically, the testable parts will expand while the untestable parts shrink.

And by adding tests for the code that has to change, you know that you're investing in the right place. You're not just picking places and fixing tech debt — you're fixing the tech debt for the places that the business (your bosses) think are important feature wise. (BTW, this might take a while to sink in...but really think about it because this is essential.)

It's not glamorous. But it works.

It's Not Just Your Code

One more thing. Technical debt isn't just a software problem. It's a systems problem. It's what happens when you optimize for short-term speed over long-term sustainability. It happens in houses. It happens in organizations. It happens in processes.

My condo's previous owners weren't stupid. They were probably doing the best they could with the time and money they had. But each "good enough for now" decision made the next decision harder, until eventually someone (me) had to deal with 120 years of accumulated "good enough."

Your codebase is the same way. Every shortcut made sense at the time. And now someone has to deal with the accumulated consequences.

The question isn't whether you have technical debt — you do. The question is whether you're going to keep putting drop ceilings on top of drop ceilings, or whether you're going to start actually fixing things.

-Ben